理財機器人並不是用來取代真人服務,而是投資人可善用機器人的大數據能力及交易紀律,克服人性貪與怕的弱點,讓投資多一個可供選擇的工具。

BARRON'S COVER

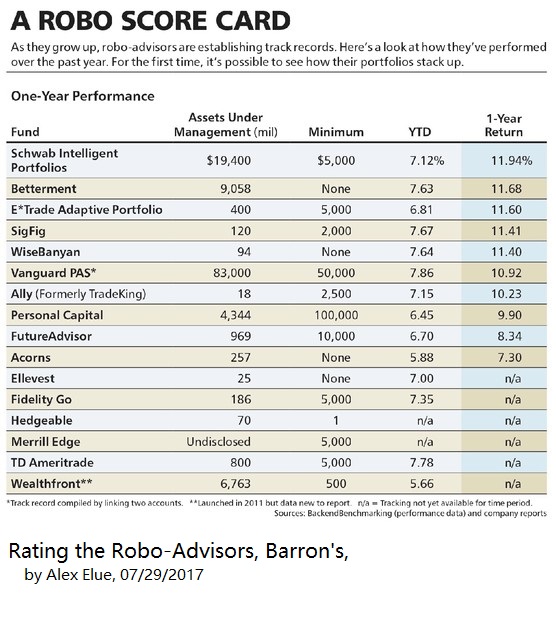

Rating the Robo-Advisors

As more investors turn to automated platforms, robos are maturing—and adding a surprising new wrinkle: the human touch.

July 29, 2017

By tech start-up standards, robo-advisors are already approaching middle age. Betterment, the pioneering robo-advisor and still the largest of the independent firms, turned seven in May. It now has $9.1 billion in assets under management.

As a business, it’s a modest success story. Many top-ranked financial advisors have far more in assets. But it’s hard to underestimate the broader impact Betterment has had on financial advice in the U.S.

The firm and its younger rivals have introduced game-changing technology to the wealth management world, similar to Tesla pushing Detroit to embrace electric cars and autonomous driving. Unlike Tesla, though, the robo-advisors haven’t built an entire car from scratch. Robo portfolios are filled with low-cost exchange-traded funds managed by fund giants like Vanguard Group and BlackRock (ticker: BLK). It would be akin to Tesla building the Model S with a Ford motor. Still, the collaboration doesn’t diminish the robos’ trailblazing ways.

“They were a kick in the pants for the industry,” says Kendra Thompson, who runs Accenture’s global wealth management practice and works with some of the largest players in the world of financial advice. “They have innovated on the client experience and proven that there’s demand for advice across all asset classes and all demographics.”

Says Betterment founder and CEO Jon Stein: “For me, one of the most satisfying results of the work we started seven years ago is seeing the entire industry change.”

Vanguard and Charles Schwab (SCHW) joined the robo movement in 2015. Their digital efforts have amassed $83 billion and $19 billion, respectively. Fidelity, Bank of America’s (BAC) Merrill Lynch unit, TD Ameritrade Holding (AMTD), and E*Trade Financial (ETFC) are more recent entrants, and Goldman Sachs Group (GS), JPMorgan Chase (JPM), and Morgan Stanley (MS) are all reportedly working on their own digital offerings.

Vanguard and Charles Schwab (SCHW) joined the robo movement in 2015. Their digital efforts have amassed $83 billion and $19 billion, respectively. Fidelity, Bank of America’s (BAC) Merrill Lynch unit, TD Ameritrade Holding (AMTD), and E*Trade Financial (ETFC) are more recent entrants, and Goldman Sachs Group (GS), JPMorgan Chase (JPM), and Morgan Stanley (MS) are all reportedly working on their own digital offerings.

The existing players are able to leverage their client relationships, which gives them a leg up in recruiting assets, and in some cases shifting assets, to their digital platforms.

“The vast majority of clients already maintain an existing relationship with Vanguard,” says Frank Kolimago, who heads Vanguard’s robolike platform, Personal Advisor Services. “They’re looking to make the relationships a bit broader.”

Tobin McDaniel, who runs Schwab’s Intelligent Portfolios robo product, says the big opportunity lies in converting investors who still use self-directed accounts. Schwab alone, he notes, has $1 trillion in self-directed accounts. “Robo advice is a much better solution for most of those people,” McDaniel says.

Meanwhile, as standalone robos have matured, they have turned to humans for help. In January, Betterment began offering human advice for a higher fee. And last week, the firm turned on a messaging service in which all of its customers can reach out to real advisors for any investing or financial-planning questions, with a response in one business day.

Meanwhile, as standalone robos have matured, they have turned to humans for help. In January, Betterment began offering human advice for a higher fee. And last week, the firm turned on a messaging service in which all of its customers can reach out to real advisors for any investing or financial-planning questions, with a response in one business day.

“The digital independent start-ups are adding human advisors, and the existing advisory firms are adding software, and we’re all ending up in the middle,” says Bo Lu, who co-founded robo FutureAdvisor in 2010 and continues to run the business, which was acquired by BlackRock in 2015.

For consumers, the middle is a good place to be: low-cost funds, managed by low-cost advisors.

BETTERMENT’S ORIGINAL robo tier, which now includes the advisor messaging service, charges one-quarter of 1% on invested assets. For a $50,000 investment, that’s $125 a year. For 0.4%, the company now offers unlimited access to human advice; customers can schedule calls as they would at traditional advisory shops.

Vanguard, which forces its digital-advice customers to run changes through a human advisor, charges an annual fee of 0.3% of assets. Traditional fee-based advisors usually charge around 1% of assets—and that’s before the cost of any funds.

The robo revolution wouldn’t have been possible without ETFs, whose fees continue to fall. The funds provide investors with inexpensive exposure to indexes that track stock and bond markets. It’s generally a passive form of investing, meaning investors aren’t picking individual winners and losers and they’re not timing the market.

Vanguard says the ETF fees for its digital portfolio average 10 basis points, or 0.1%. That gives Vanguard’s service an all-in cost of 0.4%, a paltry $200 a year for a $50,000 account.

THE PASSAGE OF TIME brings another important ingredient to the robos: performance history. For the first time, most of the robos now have a track record that’s a year or more. And Barron’s has a comprehensive look at how they’re doing, thanks to groundbreaking data from BackendBenchmarking, a Martinsville, N.J.–based analytics firm.

Backend began publishing its “Robo Report” in October 2016. Its latest quarterly report will be released to subscribers this week (the subscription is free at backendbenchmarking.com), but Barron’s got an exclusive first look.

Over the past year, Schwab’s Intelligent Portfolios robo has been the top performer, by a narrow margin. Its portfolio gained 11.94%, edging out Betterment (11.68%) and E*Trade (11.60%).

Robos are building long-term portfolios, so one-year performance is an incomplete picture. But it begins to give a basis for comparison. Perhaps, more importantly, Backend’s data is opening a window into how the robos craft their portfolios and how their decisions affect returns.

Robos are building long-term portfolios, so one-year performance is an incomplete picture. But it begins to give a basis for comparison. Perhaps, more importantly, Backend’s data is opening a window into how the robos craft their portfolios and how their decisions affect returns.

In order to track the robos’ otherwise opaque performance numbers, the research outfit opened and funded accounts at 16 different robo-advisors. It answered the robos’ risk surveys with the aim of creating a portfolio that consisted of 60% equities and 40% bonds, a time-tested approach for moderate and somewhat risk-averse investing. (The firm separately opened retirement accounts with more-aggressive allocations.)

“It started out as an experiment in the garage,” says Ken Schapiro, publisher of BackendBenchmarking. “All this money is going into these robo investments, but there was no track record. It’s a black box.”

PERFORMANCE HAS ALWAYS BEEN a touchy issue with financial advisors, who argue that customized portfolios shouldn’t be compared with other accounts. Schapiro, who also runs Condor Capital Wealth Management, a Barron’s-ranked advisor with almost $1 billion in assets, thinks all advisors should have some form of performance tracking, along the lines of what Morningstar does for mutual funds and ETFs.

Sure enough, the robo firms haven’t always celebrated Backend’s efforts. Vanguard asked to be removed from the report, and it pulled one of Backend’s accounts from its automated platform. Backend immediately picked up coverage from a backup account. The firm says it’s committed to being an independent source of data, and it’s not asking for permission to track the robos.

The company also faced some early backlash from Wealthfront, which felt that Backend had unfairly calculated its performance. Wealthfront was removed from the report soon after. Backend corrected the issue, which came in one of its first reports, and calls the experience a “growing pain.” Wealthfront has been added back to the latest report.

Betterment points out that BackendBenchmarking’s report doesn’t pick up the nuances in an advisory relationship—tax-advantaged decision making, for instance. The nuances are what Vanguard calls “advisor alpha”—which it calculates can add about 3% to the returns of advisor-managed portfolios.

Schapiro isn’t claiming that Backend’s performance numbers should be the only factor in choosing a robo-advisor: “I would say: Use it as a guideline.”

NICHOLAS JASINSKI contributed reporting to this story.

http://webreprints.djreprints.com/4205500991639.html